On July 16, 2009, the International Herald Tribune (now the International New York Times) published a little confessional essay of mine in its Op-Ed pages. I received compliments from a couple of American subscribers at Anatolia College in Greece, where I was teaching English, a piece of fan mail from a woman in Amsterdam, and a check from the IHT. End of story.

Until a week ago, when I mentioned “Render Unto Larry’s” to my girlfriend Amelia. She googled it in my presence. A link to its original appearance was the top hit. But not the only one.

“What this?” she asked. “‘Holland’s purpose in telling the general public’… It’s from a site called Course Hero.”

“What’s going on?” I wondered out loud.

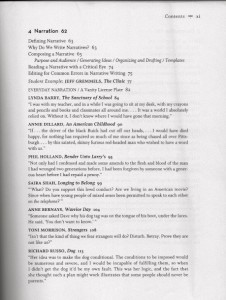

Lower down in the search results we found the answer: there was my essay listed in the Table of Contents of the 2nd edition of Back to the Lake: A Reader for Writers, ed. Thomas Cooley, an anthology published by Norton in 2011 for the college market. The rest of the links came from various student papers and study guides that had made their way online. We could access online only the Table of Contents of the antho logy, but I was able to see the names of some heavy hitters (Dillard, Russo, E.B. White) in proximity to my own. The publisher had neglected to inform me that I had become a classic author. I suppose the Times had given permission to reprint my piece. No mysterious royalty payments have arrived in my bank account. I was the last to know.

logy, but I was able to see the names of some heavy hitters (Dillard, Russo, E.B. White) in proximity to my own. The publisher had neglected to inform me that I had become a classic author. I suppose the Times had given permission to reprint my piece. No mysterious royalty payments have arrived in my bank account. I was the last to know.

The student search results were more productive: “‘Render Unto Larry’s,’ Strategies and Structures,” for example, by Alexia Hankerson for Course Hero. I could only view 2/3 of the first page without paying for further access, but Hankerson seems to be helping others with their homework (for a fee). “Holland’s purpose for telling the general public about ‘the first time’ he confessed to stealing from Larry’s is because it was more difficult the first time he wanted to make amends.” The thrill of seeing my name in the third person, as a man with a purpose no less, quickly faded as the sentence grew murky, beginning at “is because.” It doesn’t speak very well for Course Hero, I’m afraid, but it is perhaps to be expected from a site which offers students 7 million course-specific, crowd-sourced study documents, one dedicated to my Larry’s piece as taught in English 103 at Northern Illinois University.

Wait, there’s more. A student named Schmicker (location, somewhere in cyberspace) wrote his first paper on my essay. He summarized it well, then said, “Reading this story, many memories from my childhood came back to me, but one in particular stood out.” My commentator was another juvenile thief, it seems, even younger than I was. He went on to tell his own story of transgression and deliverance, which shows the influence of Holland on Schmicker. Perhaps he was a student at Illinois Valley Community College (I seem to be well liked in Illinois), which assigned my essay in English 1001 in the fall term of (no year given). Meanwhile, at Sowela Technical Community College in Lake Charles, Louisiana, students were called on to discuss Holland’s use of dialogue and point of view as they relate to the definition of the narrative essay. After learning about the “success story” formula used by Franklin in his Autobiography, they are told that “one reading which uses a variation on this pattern is Phil Holland’s ‘Render unto Larry’s’.” Franklin is actually in my story in the form of the face with pursed lips on the hundred dollar bill.

“Larry’s” also shows up as a 3-page homework assignment in Miss Abram’s honors English class at Wissahickon High in a suburb of Philadelphia. Miss Abram assigned, besides essays on me, Shakespeare, and other distinguished authors, the following intriguing paper topic:

Write a one-paragraph essay proving the thesis below. Pick two sins and give examples from the text that prove your thesis. Thesis: The members of St. Mary’s of the Immaculate Conception Church are very sinful, indeed.

Kinky! Especially for a public school. But I see now that the assignment refers to an article in the Onion that also landed in Narrative.

Amelia clicked on another link and found “Larry’s” coupled with an essay by Toni Morrison at St. Clair County Community College in Port Huron, Michigan. The next entry transported us to the English 103 syllabus at McCook Community College in McCook (pop. 7,698), Nebraska.

And there the trail ended, in the middle of the Great Plains.

I ordered a second-hand copy of Back to the Lake. It just arrived. I see that it is not unlike the anthology that I have been using this term at the Bennington branch of the Community College of Vermont, except that I am in it. There is even a brief biography, lifted, it seems, from the website of TESOL Macedonia-Thrace, on whose board I once sat. And, of course, my essay is accompanied by a battery of thoughtful study questions about Holland’s purpose, point of view, etc.

Before you rush to order Back to the Lake, I must advise you to seek out the 2nd edition; “Render Unto Larry’s” has unfortunately disappeared from the 3rd. Sic transit gloria.

ng, which gushes from the mountainside, forms a year-round pool, then begins a seasonal brook 150 yards from the house along a trail through the woods, our first trail as it was our first drinking water; the beautiful, rugged sitting-rock that dominates a slope along the trail where there used to be a glade or small wet meadow large enough for a woodcock to make its nuptial flights there in our earliest years when the forest was younger – now it is closed in, but I have been reclaiming the open area (I cut four trees there today), the better to let the bulbs I planted by the rock last fall, as Holly used to do, get sunlight enough to become established, and to create a temple (to her memory) in the woods. There are purple crocuses there now, with other flowers on the way. If this were a West Mountain theme park, that would be Holly’s Rock on the Heritage Trail. Nearer to the house are the four garden plots, and I am going to give the asparagus trenches prepared 30 years ago a try this year with 25 crowns of Purple Passion from Jo

ng, which gushes from the mountainside, forms a year-round pool, then begins a seasonal brook 150 yards from the house along a trail through the woods, our first trail as it was our first drinking water; the beautiful, rugged sitting-rock that dominates a slope along the trail where there used to be a glade or small wet meadow large enough for a woodcock to make its nuptial flights there in our earliest years when the forest was younger – now it is closed in, but I have been reclaiming the open area (I cut four trees there today), the better to let the bulbs I planted by the rock last fall, as Holly used to do, get sunlight enough to become established, and to create a temple (to her memory) in the woods. There are purple crocuses there now, with other flowers on the way. If this were a West Mountain theme park, that would be Holly’s Rock on the Heritage Trail. Nearer to the house are the four garden plots, and I am going to give the asparagus trenches prepared 30 years ago a try this year with 25 crowns of Purple Passion from Jo hnny’s. The outhouse (with no front door and a window filled with marbles); the henhouse and goat shed attached to it; the cabin, restoration of which I began last year and is this year’s project; the woodpiles, crazily multiplying in every direction; the lawn with its flat stones and solar panels; the house, now with a stone wall in front; the boulder with its high vault of maples; the standing-stone trail to the largest, highest glacial boulder just over our line and thence to the upper spring, our never-failing gravity-fed water source; the figure 8 trail to the top of the property and around down across the seasonal brook back toward the house or field, depending on whether you cut over through the beeches by the huge oak not far from the house, though still in the woods, which was the first shrine: I clear-cut the small trees around the base of it in a circle, now restored; the field itself, the forest temple above it once home to a camping adventure; the maple woods and broad main trail above the Ketterers leading back up to the meadow-that-was and Holly’s Rock. Those are the major points of interest in this Wood – other than the woods themselves.

hnny’s. The outhouse (with no front door and a window filled with marbles); the henhouse and goat shed attached to it; the cabin, restoration of which I began last year and is this year’s project; the woodpiles, crazily multiplying in every direction; the lawn with its flat stones and solar panels; the house, now with a stone wall in front; the boulder with its high vault of maples; the standing-stone trail to the largest, highest glacial boulder just over our line and thence to the upper spring, our never-failing gravity-fed water source; the figure 8 trail to the top of the property and around down across the seasonal brook back toward the house or field, depending on whether you cut over through the beeches by the huge oak not far from the house, though still in the woods, which was the first shrine: I clear-cut the small trees around the base of it in a circle, now restored; the field itself, the forest temple above it once home to a camping adventure; the maple woods and broad main trail above the Ketterers leading back up to the meadow-that-was and Holly’s Rock. Those are the major points of interest in this Wood – other than the woods themselves.

t. I may or may not light another one this evening. But I remember how close I felt to Fire last February. That was more like survival than housekeeping, though. I am ready!

t. I may or may not light another one this evening. But I remember how close I felt to Fire last February. That was more like survival than housekeeping, though. I am ready!