Δ – Delta is for Diaspora

It’s a Greek word meaning dispersion, literally, the scattering of seed in sowing, and it’s applied metaphorically (but not altogether) to human populations. You may have seen references to the Greek Diaspora, the emigration of Greeks from their homelands to start new lives in North and South America, Egypt, Australia, and Europe beginning in the 1890s – when prices for currants plunged in the Peloponnesian peninsula – and continuing into the early 20th century, when one in four young men left the country, with a second wave after World War Two, including to countries in Europe such as Germany and to Astoria in Queens, New York. And there is a third wave going on right now, a brain drain, unfortunately, as many of the educated leave the country in search of jobs in Europe, the Arab states, Australia, and to a modest degree the US.

OK, but let’s take the long view. Here’s a picture of Greece and its colonies in the 7th century BC. You can see how dispersed they were, from Marseille to the fringes of the Black Sea. Individual Greek city states had colonies or stations, and this dispersion was the result of economic activity based on maritime trade. There was no Greece as such, but there was a more or less common culture. The city states consulted the same oracles and sent athletes to the Olympic Games, founded in 776 BC in Olympia. And they could mostly understand each other’s dialects of Greek. Many of those Greek settlements lasted into the 20th century.

You can see how dispersed they were, from Marseille to the fringes of the Black Sea. Individual Greek city states had colonies or stations, and this dispersion was the result of economic activity based on maritime trade. There was no Greece as such, but there was a more or less common culture. The city states consulted the same oracles and sent athletes to the Olympic Games, founded in 776 BC in Olympia. And they could mostly understand each other’s dialects of Greek. Many of those Greek settlements lasted into the 20th century.

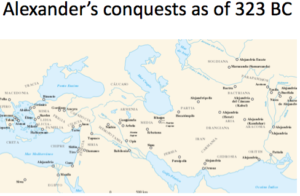

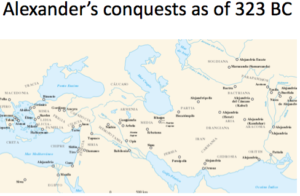

Here’s another diaspora. It’s now the 4th century BC, Philip of Macedon has conquered the other Greek mainland city states and his son Alexander has conquered everything in his path eastward all the way to the Hydaspes River in India. This territory becomes the Hellenic world, a series of Macedonian colonies where Greek became the common language. This was the world into which Christianity emerged and why the New Testament was written in Greek.

BC, Philip of Macedon has conquered the other Greek mainland city states and his son Alexander has conquered everything in his path eastward all the way to the Hydaspes River in India. This territory becomes the Hellenic world, a series of Macedonian colonies where Greek became the common language. This was the world into which Christianity emerged and why the New Testament was written in Greek.

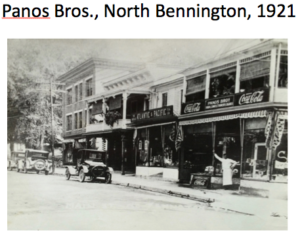

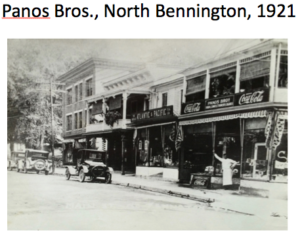

So dispersion is part of Greek cultural DNA from way back. It was economic opportunity that that induced a man named Panagiotis Panagiotopoulos — Peter Panos as he or an immigration  officer at Ellis Island shortened it — to join his elder brother George in America in 1910. He was only 12 years old. He came over with his grandmother, and he brought with him his mandolin. After a stay in Schenectady, NY, the brothers moved to North Bennington, where they were the only Greeks in what had become a mostly Catholic village, the result of 19th century European immigration to the area, where factories were then thriving and in need of laborers. Peter and George did not wish to work in a factory, however, and like so many other Greeks, they set up an eating establishment.

officer at Ellis Island shortened it — to join his elder brother George in America in 1910. He was only 12 years old. He came over with his grandmother, and he brought with him his mandolin. After a stay in Schenectady, NY, the brothers moved to North Bennington, where they were the only Greeks in what had become a mostly Catholic village, the result of 19th century European immigration to the area, where factories were then thriving and in need of laborers. Peter and George did not wish to work in a factory, however, and like so many other Greeks, they set up an eating establishment.

They must have prospered, because they soon expanded to new quarters in the heart of the little Main Street commercial district. They made candy, sold cigars, had a soda fountain and served ice cream, did some short order cooking, had at one time a pool hall and some pinball machines – Norman Rockwell’s world, but with Greeks behind the counter.  George moved to Bennington, but Pete stayed where he was and, with his new Greek wife had three daughters and a son, Louis. But the son had no taste for serving ice cream. He wanted to become a musician (in fact, all the children became musicians, and one played in the Boston Symphony). He and his North Bennington friend Laurie Hyman, son of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman, formed a jazz band (I believe it was called the Root-toot-tooters) and toured in Europe at one point.

George moved to Bennington, but Pete stayed where he was and, with his new Greek wife had three daughters and a son, Louis. But the son had no taste for serving ice cream. He wanted to become a musician (in fact, all the children became musicians, and one played in the Boston Symphony). He and his North Bennington friend Laurie Hyman, son of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman, formed a jazz band (I believe it was called the Root-toot-tooters) and toured in Europe at one point.

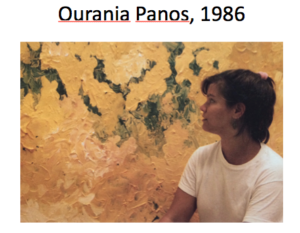

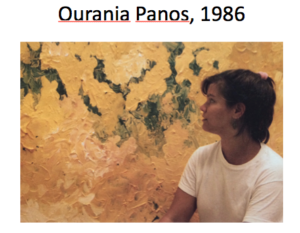

Louis served in the Air Force during the Korean War and then studied Music at Bennington College on the GI Bill. He married a Greek girl from Athens named Eleni and became a teacher, and when their elder daughter Ourania was 16 years old I got a call from Eleni requesting that she be admitted to the summer program (the July Program) I was directing at Bennington College. The program was already full, but I couldn’t resist the story and found a place for her. Ourania flourished at the program, especially in Alba de Leon’s painting class. Here is a painting she executed as the program drew to a close. I was so impressed that I purcha sed it for the College’s collection. It now hangs in the Visual and Performing Arts Center, and I doubt few suspect that it was painted by a 16-year-old.

sed it for the College’s collection. It now hangs in the Visual and Performing Arts Center, and I doubt few suspect that it was painted by a 16-year-old.

In any case, I got to know the family, and when Bennington College blew up in the mid-90s, my wife and I thought that a break would do us good. The Panoses provided the tip that sent us and our two children off for a three-year adventure at an American-founded school in Greece.

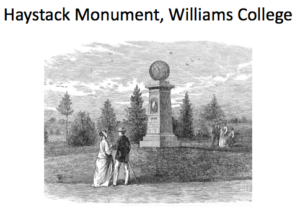

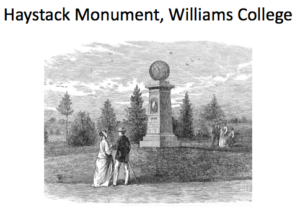

Now, how did that school get to be there? There’s another local connection and another diaspora. In 1806 a group of devout young Williams College students went for a walk in the fields near the College. A thunderstorm struck, and they took refuge under the eaves of a haystack. By the time the thunder had finished speaking to them, the young men had decided to bring the Gospel to every corner of the world.  Their movement, the American Protestant missionary movement, later based in Boston, was a kind of global American diaspora of liberally educated men of the cloth. One of their targets was the Ottoman Empire.

Their movement, the American Protestant missionary movement, later based in Boston, was a kind of global American diaspora of liberally educated men of the cloth. One of their targets was the Ottoman Empire.

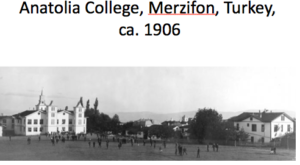

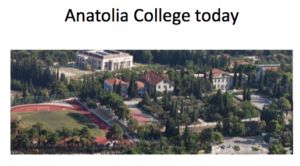

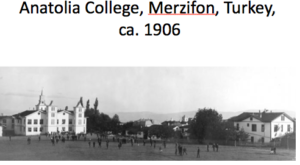

They failed to convert the Muslims, but they were welcomed by the Christian minorities of what is now Turkey, that is, by the Armenians and the Greeks, to whom they provided a general American-style education in schools and colleges and from whose population they recruited and trained native Protestant priests.  The schools flourished, but things didn’t end happily: in the early 20th century Anatolia College was witness to the Armenian genocide and the genocide of the Greeks of the Pontus region in Turkey, near which the College was located. American schools and missions were expelled from that part of Turkey in 1922,

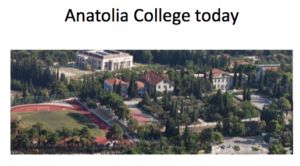

The schools flourished, but things didn’t end happily: in the early 20th century Anatolia College was witness to the Armenian genocide and the genocide of the Greeks of the Pontus region in Turkey, near which the College was located. American schools and missions were expelled from that part of Turkey in 1922,  but Anatolia re-established itself in Thessaloniki as a wholly secular institution. Seventy-some years later, my family and I arrived there as one small result of all the diasporas I’ve mentioned.

but Anatolia re-established itself in Thessaloniki as a wholly secular institution. Seventy-some years later, my family and I arrived there as one small result of all the diasporas I’ve mentioned.

with enough of a common cultural past to induce member states to give up some of their sovereignty in order, for one thing, to stand up to the other economic heavyweights of the world – and also not to fight each other any more. Former French president Giscard d’Estaing spoke of the “Dream of Europe. Let us imagine a continent at peace, freed of its barriers and obstacles, where history and geography are finally reconciled.”

with enough of a common cultural past to induce member states to give up some of their sovereignty in order, for one thing, to stand up to the other economic heavyweights of the world – and also not to fight each other any more. Former French president Giscard d’Estaing spoke of the “Dream of Europe. Let us imagine a continent at peace, freed of its barriers and obstacles, where history and geography are finally reconciled.”

BC, Philip of Macedon has conquered the other Greek mainland city states and his son Alexander has conquered everything in his path eastward all the way to the Hydaspes River in India. This territory becomes the Hellenic world, a series of Macedonian colonies where Greek became the common language. This was the world into which Christianity emerged and why the New Testament was written in Greek.

BC, Philip of Macedon has conquered the other Greek mainland city states and his son Alexander has conquered everything in his path eastward all the way to the Hydaspes River in India. This territory becomes the Hellenic world, a series of Macedonian colonies where Greek became the common language. This was the world into which Christianity emerged and why the New Testament was written in Greek. officer at Ellis Island shortened it — to join his elder brother George in America in 1910. He was only 12 years old. He came over with his grandmother, and he brought with him his mandolin. After a stay in Schenectady, NY, the brothers moved to North Bennington, where they were the only Greeks in what had become a mostly Catholic village, the result of 19th century European immigration to the area, where factories were then thriving and in need of laborers. Peter and George did not wish to work in a factory, however, and like so many other Greeks, they set up an eating establishment.

officer at Ellis Island shortened it — to join his elder brother George in America in 1910. He was only 12 years old. He came over with his grandmother, and he brought with him his mandolin. After a stay in Schenectady, NY, the brothers moved to North Bennington, where they were the only Greeks in what had become a mostly Catholic village, the result of 19th century European immigration to the area, where factories were then thriving and in need of laborers. Peter and George did not wish to work in a factory, however, and like so many other Greeks, they set up an eating establishment.

sed it for the College’s collection. It now hangs in the Visual and Performing Arts Center, and I doubt few suspect that it was painted by a 16-year-old.

sed it for the College’s collection. It now hangs in the Visual and Performing Arts Center, and I doubt few suspect that it was painted by a 16-year-old.

but Anatolia re-established itself in Thessaloniki as a wholly secular institution. Seventy-some years later, my family and I arrived there as one small result of all the diasporas I’ve mentioned.

but Anatolia re-established itself in Thessaloniki as a wholly secular institution. Seventy-some years later, my family and I arrived there as one small result of all the diasporas I’ve mentioned.

and olives can live 3000 years, like this one in Crete (at Vouves).

and olives can live 3000 years, like this one in Crete (at Vouves).